After a honeymoon trip to California and the Southwest in 1902, Charles Francis Saunders and his first wife Elisabeth moved to California permanently, settling in Pasadena in 1906. Back home in Pennsylvania they were avid naturalists and collaborated on horticultural publications, Charles doing the writing and Elisabeth, the illustrations. After their arrival in California, they shifted their focus to travel writing. Saunders tripped extensively throughout California, both with Elisabeth and with his second wife Mira. All were amateur photographers. Saunders had work published in magazines like Travel, Country Life in America, and Sunset. He would go on to write over a dozen books on California, illustrating them with the photographs taken by him and his wives. His publications include titles such as Under the Sky in California (1913), Finding the Worthwhile in California (1916), The Southern Sierras in California (1923). As much of a pyschological guide to California as a practical one, Saunders dedicates Under the Sky in California “to the Tenderfoot, whom California loves to educate”, encouraging travelers to venture off of the beaten track. Saunders preferred a horse and carriage to an automobile, but he still relied on roads and he includes detailed instructions for following them. Hired horse Gypsy Johnson features frequently in the chapter titled “Spring Days in a Carriage” in which Charles and Elisabeth take a road trip based on Helen Hunt Jackson’s 1884 classic novel Ramona. In his chapter “The Deserts'' Saunders writes rapturously about the spiritual gifts given to those that seek a true connection to nature, and footnotes it with his entire packing list.

“On this experimental trip we learned some simple fundamental facts about the desert. Its most beautiful hours are from dawn until ten in the morning, and from four or five in the afternoon until nightfall. During these periods at the season of the year when we were there, the atmosphere was more of heaven than of earth. The glowing sky, radiant with sunrise and sunset glories; the unspeakable opalescent tints on distant mountains; the brilliant flowers blooming upon the sands at one’s feet; a sense of largeness and indifference to petty things-these are the gifts of the desert’s mornings and evenings never to be forgotten. Then, to crown all, there is the night-serene, starlit, full of peace, its solemn stillness broken only by the lament of some owl far or near, or the cry of coyotes hunting. And over and beyond these recitable matters there is an unutterable something that tugs at the heart of the true desert lover, and makes him long evermore for its silent places. For it is not merely what the outward eye takes in that urges us on to visit certain regions-it is the residence there of intangible influences that feed our spirits with manna from the secret storehouses of the universe, making us for the time partakers of an unseen feast of life with the Master Himself. During these night watches on the desert, the veil between this world and the spiritual seems thinner than elsewhere, and in some measure comprehends why prophets of all time have found inspiration and strength in desert regions. Here in these waterless wastes, the wine of a spiritual kingdom is poured abundantly and the awakened soul hears the summons to a new life....Then when the sun has gone to his setting, there is the drive home in the quiet afterglow, with the palpitating light of the first star burning in the twilight sky, and all the earth baptized for a brief space into a heavenly peace, before the night shall shut in.“

Saunders was a member of an informal group of like minded artists/writers/wilderness lovers in Southern California now referred to as the Creative Brotherhood. The group included painter Carl Eytel, commercial photographer Avery E. Field, biologist Edmund Jaeger, as well as writer/photographers Joseph Smeaton Chase and George Wharton James. They built a colony of cabins at the base of Mount San Jacinto, traveled together, and philosophized about the glory of nature. In California, Romantic And Beautiful (1914) George Wharton James writes, “I have watched Carl [Eytel] on the desert, racked with a hacking and persistent cough, tramping miles and miles over the weary, hot, sandy plains, and then so eager to transcribe for the world the glory of colour revealed only in these secret places that he would tremble with the glory and passion that had taken possession of him.” The men often published each others work. Jaeger’s Denizens of the Desert (1922) contains illustrations by Wright M. Pierce, Eytel, Edwin A. Field, and Smeaton Chase. In 1915 Saunders collaborated with Smeaton Chase on California Padres and Their Missions.

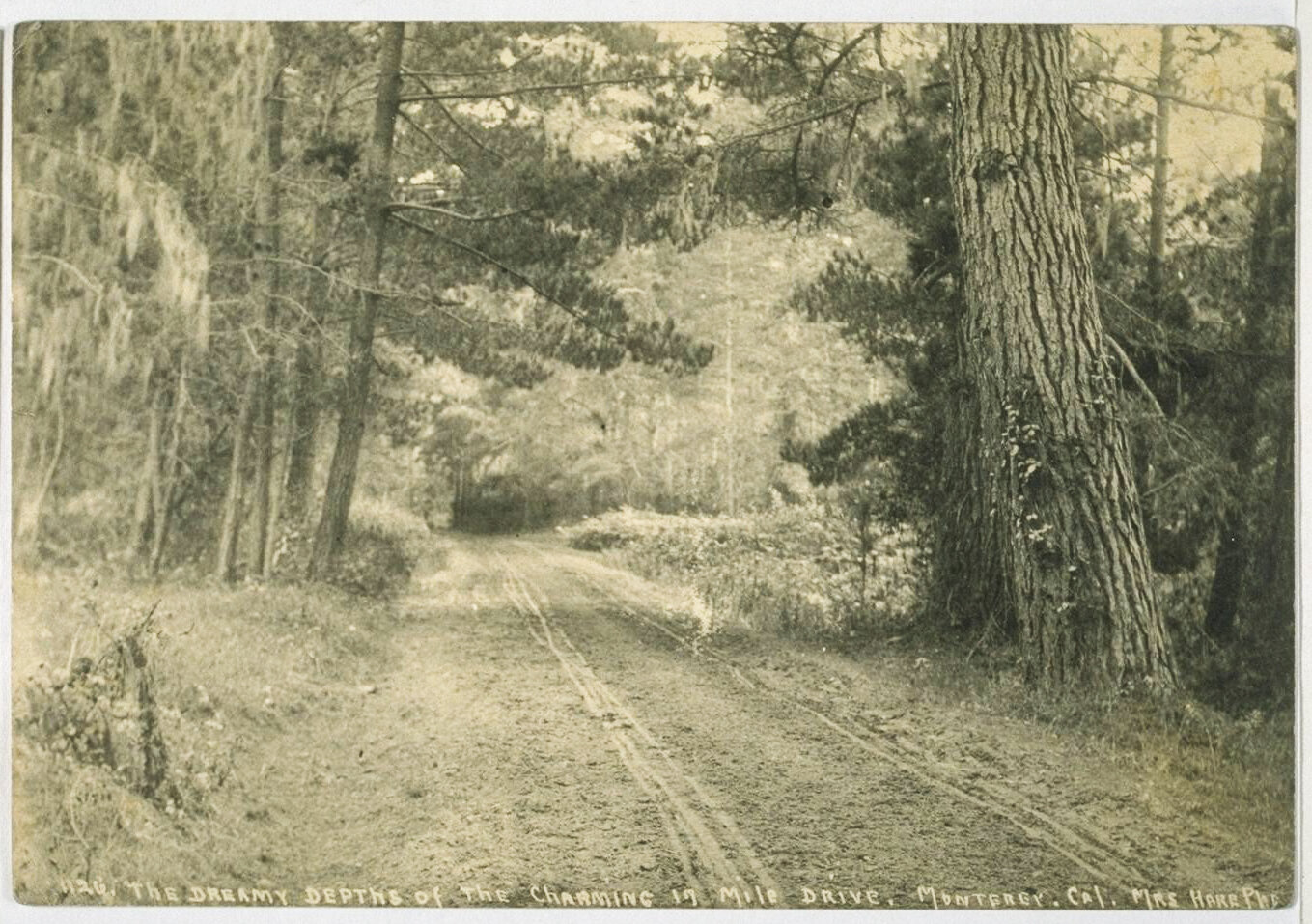

J. Smeaton Chase emigrated to California from London in 1890. He was 25. Drawn to isolated areas, he did much of his traveling by horse. He traveled the San Jacinto and Santa Rosa mountains with his burro, Mesquite, in 1915. In California Coast Trails: a Horseback Ride from Mexico to Oregon, Smeaton Chase describes approaching the Pacific from the San Lucia mountains, “Higher still, and near the crest, I came into a region of magnificent yellow pines and redwoods. It was sundown, and the view was a remarkable one. The sun shone level, and with a strange bronze hue, through a translucent veil of fog. Below the fog the surface of the ocean was clear, and was flooded with gorgeous purple by the sunset. On the high crest where I stood, a clear, warm glory bathed the golden slopes of grass and lighted the noble trees as if for some great pageant. There was a solemnity in the splendor, an unearthly quality in the whole scene; that kept me spellbound and bareheaded until, fatefully, imperceptibly, the sun had set.” Smeaton Chase’s other books include Cone-bearing Trees of the California Mountains (1911), Yosemite Trails: Camp and Pack-train in the Yosemite Region of the Sierra Nevada (1911), The Penance of Magdalena: And Other Tales of the California Missions (1915), California Desert Trails (1919), and Our Araby: Palm Springs and the Garden of the Sun (1920). He also contributed photographs to John Van Dyke’s The Desert: Further Studies in Natural Appearances (1918).

![I would rather sit on a pumpkin and have it all to myself than to be crowded on a velvet cushion [No. illegible]. Alice Iola Hare Photograph Collection, BANC PIC 1905.04663-05242, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59ac4de9579fb343a2d7737d/1606019131777-CIOW472711WFMMKVA21I/hare_3.jpg)